I saw this Virgin Mary image during a recent trip to Colorado and Utah, where the dramatic and ancient landscapes hold many forms and faces. But, of course, what I recognize as a visual manifestation of a religious or secular icon in stone has existed since well before humans and religions. In many of the Madonna of the Toast stories, people see Jesus or the Virgin Mary in a tree or rock, but in the shadow of such grandeur of places like Natural Bridges, Valley of the Gods and Canyonlands I couldn’t help but ponder myth and how it is made visual, and recognizable.

Along with the spires of red rock stacked like totem poles (replete with human-esque faces) and towering canyon walls that reveal millions of years worth of geological history, screaming with Edvard Munch faces, myth cannot be ignored when you also consider the abundance of the region’s petroglyphs and pictographs, most of which were left by the Anasazi (a Navajo word meaning “ancient ones”). I first learned of the Anasazi years ago when I met photographer Nathan Troi Anderson, a very good friend of mine and the impetus for this trip. I had seen his photographs of these symbols, but had never had the chance to look at them in situ. While I’m no expert on the Anasazi, or the American Southwest for that matter, it wasn’t hard for me to put the two subjects within a Madonna of the Toast context.

The exact meanings of these ancient symbols are difficult to define, especially since the Anasazi more or less disappeared, leaving little more than these markings, some structures and various artifacts. But standing in these stunning canyons, looking at the natural contours of stone weathered by time, it is clear that the manmade images respond directly to these natural environments, for it is all these people knew. It was through their interactions with the land, the sky and the seasons that the meaning of life took shape. The shape of these meanings, whatever they might be, are seen in lightning bolt lines, dizzying circles and majestic shaman forms. This is the stuff of myth.

When I saw the Virgin Mary shape in Utah, it was myth speaking to me, though in this case the myth is not as old as the form. For its relative youth, on a geological scale as well as human scale, Christian mythology, particularly that of the Virgin Mary, has proliferated over time. When you consider that Mary is mentioned only 19 times in the Bible (she is mentioned 34 times in the Qu’ran) her popularity is astounding. What do we make of this?

No matter when they came into being or where they were located, all human cultures have their own creation stories in which a mother figure plays a central role. With the Anasazi, as one example, feminine forms are not hard to discern in the petroglyphs and pictographs. Their importance is also bolstered by the belief that the Anasazi held their most sacred ceremonies in manmade ritual caves, or kivas. These areas were built underground so participants would have to go down into them and then later emerge, much like a child exiting the womb.

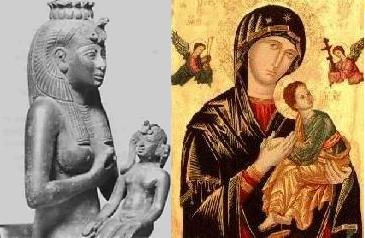

From both the literal and figurative perspectives, the Christ story also possesses this maternal quality, which was recognized and elaborated as Christianity spread. In fact, Western interest in Mary did not flourish until the 12th century, though the power of her myth was recognized all along. According to this Maclean's article, “when nascent Christianity spread to Egypt and encountered the cult of Isis, mother of the god Horus, Mary’s status began to rise even higher. Isis was a powerful and kind-hearted deity, attributes Mary soon acquired.”

The article is essentially a review of Miri Rubin’s Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary, which apparently identifies the real power of the Mary myth:

[T]ension—poised between virgin and mother, human and divine—is the source of her endless variety of portrayals, all gracefully traced by Rubin, from the young, sometimes playful, virgin girl to the grief-stricken and empathetic mother at Calvary. The need to ground Mary explains why she did die, as befits a mortal, but was raised bodily to heaven, as befits the mother of God . . . But there was a Mary for everyone, not just motherless clerics, in the flowering of medieval Mariology. For every image of a heavenly queen commissioned by wealthy art patrons, there was a story of the humble carpenter’s wife, particularly gracious to the poor and those who suffered.

This dovetails perfectly with the Madonna of the Toast mantra: What do you see? Throughout time, whether in the form of ancient inscriptions or Biblical stories, the visual manifestations of mythic iconic forms have endured the tests of time because they can represent a range of meanings, depending on the viewers. And while interpretations of the images may vary, they all demonstrate the human need for asserting our presence in this mysterious world where answers are nowhere near as important as interpretations.

2 comments:

Hola Amigo,

My name is Richard I live in the USA (San Francisco) You and I need to talk. I also discovered the Helmet hidden in the davinci painting. We actually do the same work. I have been exploring symmetry for some time check out my website richardtmonk.com or my blog at mirrorimageart.blogspot.com

I have made some very positive inroads concerning this subject and maybe you would be interested. Email me and we can talk. Thanks

I've been searching & yearning to know more of the Mary Myth. I'm glad I was lead here first. I have collected variations of the Madonna for quite a while and I always seem to question myself why.. and I know there is a reason and I know its purposeful.

Myth is important to us as a humanity. The recession of myths have made our imaginations seemingly more bare-boned, metaphors only seem to have one strong connotation. Humanity has dumbed down our senses and aren't as receptive to images that are eyes don't see.. but our spirit does. [like the one you saw in the rock].

It's not about seeing what you see... its seeing what you don't see, that which you know is there.

Post a Comment